Many stories about Mühlenstraße from before the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 still remain untold. Although no structural traces of that time survive, historical photographs and documents provide clues to those who once lived and worked there.

Rubber Goods from Mühlenstraße – Colonialism on Mühlenstraße

One of the first German gutta-percha factories was established in 1843 at Mühlenstraße no. 70/71 (the two buildings seen on the left edge of the aerial photograph). The company, founded by W. Eliot, merged with other companies in 1870 to form the Berlin rubber goods factory. It, in turn, became the Vereinigte Berlin-Frankfurter Gummiwarenfabrik in 1886 and, the Veritas Gummiwaren AG in 1929. In 1927, the property on Mühlenstraße was sold and the company headquarters moved to Lichterfelde. "Veritas" joined forces with "IG Farben" to develop a new synthetic rubber. The company began specializing in tire production and is still active in this field.

Gutta-percha and caoutchouc were essential materials in the production of rubber. Rubber, in turn, was a key raw material in the development of Germany’s industry. It was used in the sheathing of electric cables and drive belts, in rubber sealing rings and car tires. Many important products in the industrialization and motorization process were made of rubber or gutta-percha.

Both of these raw materials were derived from the milky sap of tropical plants and was only available outside of Europe. Germany was able to obtain this raw material cheaply – from its own colonies in East Africa—including today's Cameroon, Tanzania and Rwanda—as well as from other European colonies. The people in South America and Africa were subjected to terror and violence and forced to extract the silky white liquid from trees. The profits reaped from this key raw material went to the European middlemen and to the companies that made rubber products, which included the factory on Mühlenstraße.

Jewish Entrepreneurship on Mühlenstrasse

At least eleven Jewish-owned companies were located on Mühlenstraße. During the Weimar Republic, Jews had the same legal status as non-Jewish Germans, but this changed once the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933. Thereafter, it became increasingly difficult—and later impossible—for Jews to lead a self-determined and free life. Under the Nazis, Jewish Germans were discriminated against and excluded from economic, social and political life. The basic rights of Jews were restricted by new laws and later eliminated altogether. A central aim of these anti-Semitic policies was to deprive Jews of their economic livelihood. The city of Berlin ended cooperation with Jewish companies and Jews were excluded from selling at local markets. Jewish entrepreneurs were harassed and forced to sell their companies. Jews and non-Jews lived and worked increasingly separate from one another. The Jews in Berlin were eventually deprived of any means to earn a living.

By 1937 at the latest, all Jewish-owned companies on Mühlenstraße had been deleted from the commercial register. Little is known about the families who had run these businesses. Some were able to leave Germany and, thus, survive the Shoah, but others stayed in Berlin until they were deported. We know of one individual, Siegfried Abramowsky, who was co-owner of a button factory on Mühlenstraße. In July 1942, at the age of 70, he was deported by the Nazis to the Theresienstadt ghetto, where he died as a result of starvation, poor hygienic conditions and a lack of medical care.

Additional information:

Death notice for Siegfried Abramowsky: https://www.holocaust.cz/de/datenbank-der-digitalisierten-dokumenten/dokument/85344-abramowsky-siegfried-todesfallanzeige-ghetto-theresienstadt/

Nazi Forced Labor on Mühlenstraße

The Nazis depended on millions of forced laborers to sustain the German economy during the war. Thirteen million women, men and children from the occupied territories of Europe were forced to work in the German Reich; this included Jews, Sinti and Roma, concentration camp prisoners, prisoners of war, and "civilian workers." Another 13 million people were forced to work in the occupied territories. The treatment of forced laborers was determined by the Nazi racist ideology: Western European workers were better fed and housed than Eastern European workers. Jews, and Sinti and Roma were subjected to the worst conditions. Soviet prisoners of war were also treated badly.

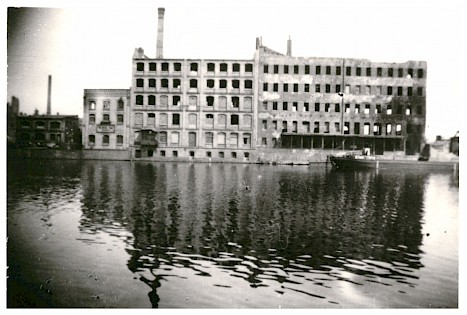

In 1943, more than half a million forced laborers lived in Berlin, including on Mühlenstraße. There is evidence that forced labor was used at the Osthafen Mill as well; documents show that prisoners of war from the camp on Kaulsdorfer Straße were sent there “on loan” in 1941.

Between 1944 and 1945, forced laborers either from the Netherlands or Belgium were housed for several months in the Eduard Müller House, the journeymen's dormitory, which belonged to the Kolping family and was located at Mühlenstraße 60 b and c. They were deployed at Siemens-Plania, a company that produced coal products that had been declared “essential to the war effort.” As Western Europeans, the forced laborers were not required to live in a barracks camp. However, they too were subject to the despotism of their employers and the Germans. They had no influence over their working conditions, nor could they change their jobs or leave Berlin without permission.

Additional information:

Information about the camp on Kaulsdorfer Straße in Berlin-Biesdorf: https://www.gedenktafeln-in-berlin.de/gedenktafeln/detail/lager-kaulsdorfer-strasse-90-stele-2/2947