Dividing the City

“The Wall is a symbol for an entire generation. To us it represented our separation and the division, even in everyday life.”

When the Berlin Wall was built on 13 August 1961, it divided Berlin into two parts. It separated families and friends, cut off people’s usual routes through the city and destroyed an intact urban infrastructure. The residents of Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg lost an important connection when the Oberbaum Bridge was sealed off. Yet residents could still live on the banks of the Spree in Friedrichshain. Although they no longer exist today, buildings with living and working space once stood along the water’s edge on Mühlenstraße. The windows were barred and makeshift barriers were added to block access to the water and prevent escape attempts. By 1977, all the buildings along Mühlenstraße had been demolished and the area was cleared to create a border strip that would make escape attempts impossible.

Working on the Border on Mühlenstraße in Friedrichshain (East Berlin)

For many, living with the Wall was a part of everyday life. Mühlenstraße was an important transport link into the city and served mainly vehicle traffic. Every day, people drove by the "Border Wall 75," which left a dreary and gray impression. The granary was the only building between Mühlenstraße and the Spree that was not demolished by GDR border troops. It belonged to the Osthafen mill across the street and was important for the GDR's flour production. The employees of the mill worked directly on the border every day. They entered the border strip through a gatehouse built into the Berlin Wall. The Stasi kept a close eye on all activity in the storehouse.

The "VEB Narva Kombinat Berliner Glühlampenwerk," a lightbulb factory in whose main building BASF now maintains its offices, stood just a few hundred meters away. More than 6,000 people worked here in the late 1970s. As in other state-owned enterprises in the GDR, company life extended deep into the private sphere. A socialist "folk culture" was meant to bridge the gap between the working class and intellectuals. The VEB Narva organized holiday camps for its employees' children and ran its own sports, leisure, culture and youth clubs. It also operated a vocational school. Cultural activities included a language school located near the border for "contract workers" who had come to the GDR from socialist brother states. Although daily life took place in close proximity to the border, approaching the border fortifications on Mühlenstraße was forbidden. The People's Police secured the area in front of the border and kept Mühlenstraße under surveillance.

Contemporary witnesses remember

The Border in Kreuzberg

“West Berlin was a real cosmopolitan village.”

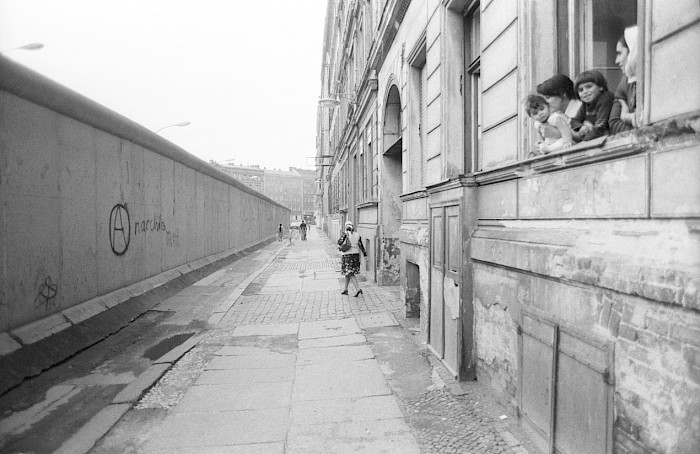

The proximity of Kreuzberg to the border and Wall was felt daily. In many places the Wall cut through residential neighborhoods and divided streets. People adjusted to the situation as best they could. For the residents of Kreuzberg, however, it also meant that their district, which had been part of the city center, was now on the periphery. This also affected the neighborhood's social fabric. Wealthier people moved to other districts and were replaced by artists, students and migrants. But unlike in Friedrichshain, the residents in Kreuzberg could approach the Wall. It was forbidden and dangerous to touch the Wall, however, because it stood on GDR territory. Yet, this didn’t stop it from becoming a canvas for messages and political slogans soon after its construction in 1961. In the mid-1970s, artists discovered that the newly erected and whitewashed "Border Security Wall 75" provided an ideal painting surface for all kinds of comments, writing and art.

“This was the end of the world. This here was free time. Over there was the Soviet Union.”

Although the Spree constituted border waters, Kreuzbergers enjoyed hanging out, fishing and playing along the riverbank. The entire width of the Spree here was GDR territory, so swimming was not allowed and even entering the water in an emergency situation was treated by the GDR as an "illegal border crossing." This often had serious consequences. Between 1966 and 1975, five children drowned near the riverbank. Andreas Senk (age 6), Cengaver Katrancı (age 8), Siegfried Kroboth (age 5), Giuseppe Savoca (age 6) and Çetin Mert (age 5) had all been playing on the embankment when they fell into the water and drowned. The GDR border troops responded too slowly, and West Berlin rescue workers were not allowed to intervene. Finally, in 1976, West Berlin and the GDR reached an agreement aimed at preventing accidents in the border river: rescue posts for emergency calls were installed and fences were erected along the riverbank.

“And then this conflict takes place. You have everything, you could help, but you are not allowed to help because it is not politically desired."

Contemporary witnesses remember

The Actionbound-Tour “SpurenWandler” offered by Kulturring in Berlin e.V. takes you on a journey of discovery along the former border in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg:

https://www.kulturring.berlin/projekte/spurenwandler

Podcastfolge zum Leben im geteilten Berlin: Die Podcast-Reihe „Grenzerfahrung“ von der Stiftung Berliner Mauer entstand 2021 anlässlich des 60. Jahrestags des Mauerbaus und wurde gefördert von der Bundesbeauftragten für Kultur und Medien. In der Folge „Alltag in Teilung“ wird darüber gesprochen, wie sich das Leben im geteilten Berlin entwickelt hat. Die hohe Betonmauer gehörte zum Alltag der Bewohnerinnen und Bewohner Berlins. Aber nicht alle Menschen wollten die Grenzabriegelung hinnehmen, sie versuchten, aus der DDR zu fliehen. Expertinnen und Experten geben Auskunft über das Grenzregime der DDR und berichten von den mindestens 101 Menschen, die bei einem Fluchtversuch ums Leben kamen oder inhaftiert wurden. https://www.stiftung-berliner-mauer.de/de/stiftung/podcast-grenzerfahrung